Klara’s Language(s)

Yes, plural: as a person who refuses to be confined to one language – my tongue must be multi-forked – I was naturally drawn to Klara’s proven skills as a multilingual teacher and translator. These skills are intertwined with her transnational identity and I certainly cannot tell you which came first, Klara’s sense as a world citizen (belonging everywhere or belonging nowhere) or her ability to fit in to diverse cultures through language. When you read her diary you will note the liberal sprinkling of words and phrases in Yiddish, French, Italian, German, Hebrew, English... Of course she wrote the diary in German, so we must suspend our disbelief as we read the English or the Spanish versions.

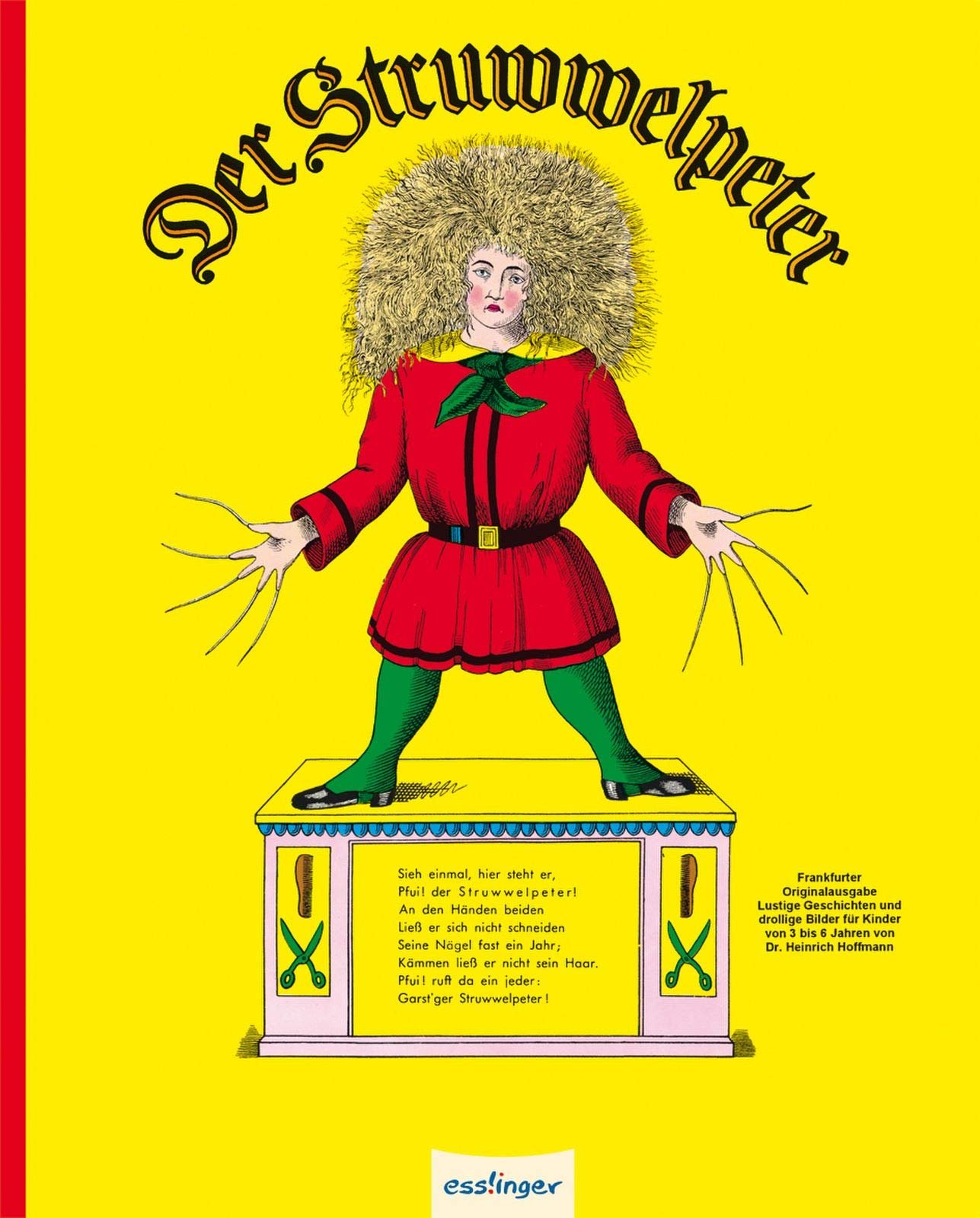

In 1925, Klara and her younger sister Gerda enroll in a Berlitz Spanish course in Berlin, in preparation for their upcoming trip to Seville, and Klara is impressed by the “direct method” of instruction, in which students hear only the target language and thus produce it “naturally.” This method will influence her own teaching style, and in the improvised German class in Ocaña she will use as a single textbook the well-worn family copy of Heinrich Hoffmann’s Der Struwwelpeter. Her four students – one doctor, one physician’s assistant, and two volunteers, learn quite a bit of German from Klara’s dramatic enactment of the opening verses.

Der Struwwelpeter, cover. Image from Amazon.com

As the war advances, Klara is more sought as a language specialist than a nurse-practitioner. This blurry paragraph at the end of a letter from Dr. Willy Glaser and Hospital Americano No. 1/Hospital Internacional in Vic, Catalunya, to the director of the AME (Ayuda Médica Extranjera – Foreign Medical Aid) says it all (my English translation first, then the Spanish transcription)

Last paragraph of letter to the AME from Dr. Willy Glaser, requesting Klara as an administrator in Vic, for her linguistic abilities. Image courtesy of Robert Llopis. The meaning of the handrritten notes cannot yet be revealed.

“Since the departure of Comrade Lieutenant Linick we need, for the Director’s office, a comrade who speaks perfect Spanish and some foreign languages and we therefore ask you to send us, if possible, Comrade Clara Philipsborn.”

“Después de la salida del camarada teniente Linick necesitamos para el despacho de la dirección un camarada que hable perfectamente el español y algunos idiomas extranjeros y es por eso que rogamos nos manden, si es posible, a la camarada CLAERE PHILIPPBOORN.”

Note the garbled spelling of Klara’s name, typical of her experience in Spain. The reference to a Lieutenant Linick is to Edgar Linick, a landsman of Klara’s (distantly related and also multilingual), who also arrived fairly early in Spain (1933) as an affiliate of the Catalonian antifascist PSUC party, and as war broke out, worked in medical care administration. After the war he was interned in several fascist prison camps, survived, and found employment in East Berlin, where he died in 1982.

Edgar Linick arrives in Spain, spring 1933. Image from http://www.stolpersteine-heidelberg.de/mediapool/63/638182/data/2020/71_Linick_Text.pdf

Another dimension of Klara’s linguistic life is suggested in this sentence, part of a post-war report on Klara that I cannot yet reveal:

“Most recently she was in Barcelona, employed in a language institute.”

“Zuletzt war sie in Barcelona in einem Sprachinstut beschäftigt.”

In her book, Irma’s Passport, Katy Ehrlich uses the metaphor of the passport to signify her grandmother’s ability to adjust to and to survive wrenching displacement and difference, through her mastery of several languages. Do you think that Klara’s language abilities will serve as her passport to survival of racism, fascism, misogyny and the Holocaust?